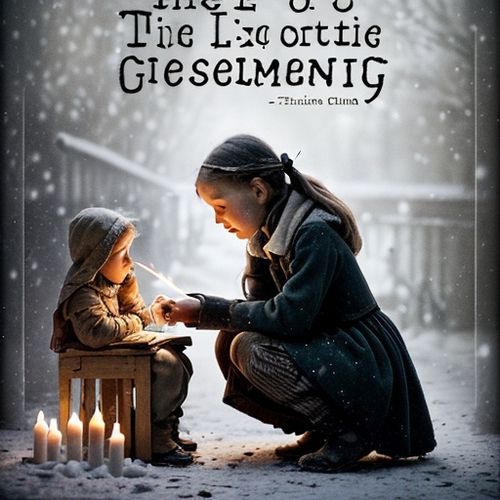

The story of the Little Match Girl, penned by Hans Christian Andersen in 1845, remains one of the most poignant tales of poverty, hope, and the human condition. Set against the backdrop of a freezing New Year's Eve, the narrative follows a young girl struggling to sell matches on the streets, her suffering a stark contrast to the warmth and festivity surrounding her. Though often categorized as a children’s story, its themes are deeply adult, exploring societal neglect, the fragility of life, and the thin line between despair and transcendence.

Andersen’s tale opens with the girl, barefoot and shivering, too afraid to return home without having sold a single match. Her father would beat her for failing, and the cold of the streets seems almost preferable to the violence awaiting her. The setting is deliberate—a festive evening where others are celebrating behind closed doors, their indifference to her plight underscoring the isolation of the poor. The matches she carries become symbols of both her desperation and her fleeting moments of solace. Each one she lights offers a vision—a warm stove, a holiday feast, a loving grandmother—only to vanish when the flame dies, leaving her in the bitter cold once more.

The visions themselves are a masterstroke of storytelling. They are not mere fantasies but a psychological escape, a way for the girl to cope with her unbearable reality. The final vision, of her deceased grandmother, is particularly haunting. Unlike the other illusions, this one lingers, suggesting that death may be the only escape for those forgotten by society. The grandmother’s appearance is tender yet tragic—she "takes" the girl away, lifting her from suffering into an ambiguous afterlife. Andersen’s prose here is sparse but devastating: "No one had the slightest thought of what beautiful things she had seen, nor in what glory she had gone with her grandmother into the New Year."

Critics have long debated whether the ending is meant to be comforting or cruel. Does the girl find peace, or is her death a condemnation of a world that allows such suffering? The story’s power lies in its refusal to provide easy answers. The religious undertones—the grandmother as a quasi-angelic figure, the "glory" of the afterlife—suggest redemption, but the girl’s lifeless body, discovered the next morning with a smile on her lips, forces readers to confront the cost of that redemption. It’s a moment that lingers, unsettling in its juxtaposition of beauty and tragedy.

Modern retellings and adaptations often soften the edges of Andersen’s original. Animated films and illustrated books depict the girl’s death as a serene passing, sometimes omitting the brutality of her circumstances altogether. Yet to sanitize the story is to miss its point. The Little Match Girl is not a fable about the rewards of innocence but a protest against systemic indifference. Andersen, who grew up in poverty himself, understood the mechanics of societal neglect. His girl is not a passive victim; her visions are acts of resistance, small rebellions against a world that has failed her.

The tale’s enduring relevance is a testament to its unflinching honesty. In an era of income inequality and homelessness, the Little Match Girl’s plight feels uncomfortably familiar. Her invisibility to passersby mirrors the way society often overlooks its most vulnerable members. The matches, cheap and ephemeral, mirror the temporary solutions offered to the poor—charity without systemic change, aid without justice. Andersen’s genius was in recognizing that the greatest horrors are not supernatural but mundane: the cold, the hunger, the loneliness that goes unnoticed.

What makes the story uniquely heartbreaking is its quietness. There are no villains, no dramatic confrontations—just a child freezing to death while the world carries on. The tragedy is in the ordinariness of it all. The girl’s death isn’t witnessed; it’s discovered after the fact, a footnote to the celebrations. This structural choice forces the reader into the role of the passerby, complicit in their inability to intervene. It’s a narrative sleight of hand that implicates us all.

Andersen’s prose, deceptively simple, carries a weight that lingers. His descriptions of the cold—the "frosty flakes" on her hair, the "copper coins" of her cheeks—are tactile and vivid. The girl’s final vision, of her grandmother lifting her into a place where "there was neither cold, nor hunger, nor fear," is rendered with a heartbreaking clarity. The story’s closing lines, noting the neighbors’ indifference to the girl’s death, land like a hammer blow. It’s a reminder that the greatest cruelty is not malice but apathy.

The Little Match Girl endures because it refuses sentimentality. It doesn’t offer easy moral lessons or false comfort. Instead, it holds a mirror to the reader, asking what we see—and what we choose to ignore. In an age of curated empathy and performative compassion, Andersen’s tale remains a challenge: to look, truly look, at those the world has left behind. The matches may burn out, but the story’s light persists, a flicker in the dark.

By Eric Ward/Apr 29, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 29, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 29, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 29, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 29, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 29, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 29, 2025

By Noah Bell/Apr 29, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Apr 29, 2025

By Olivia Reed/Apr 29, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 29, 2025

By Natalie Campbell/Apr 29, 2025

By Noah Bell/Apr 29, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 29, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 29, 2025

By Laura Wilson/Apr 29, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 29, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 29, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 29, 2025